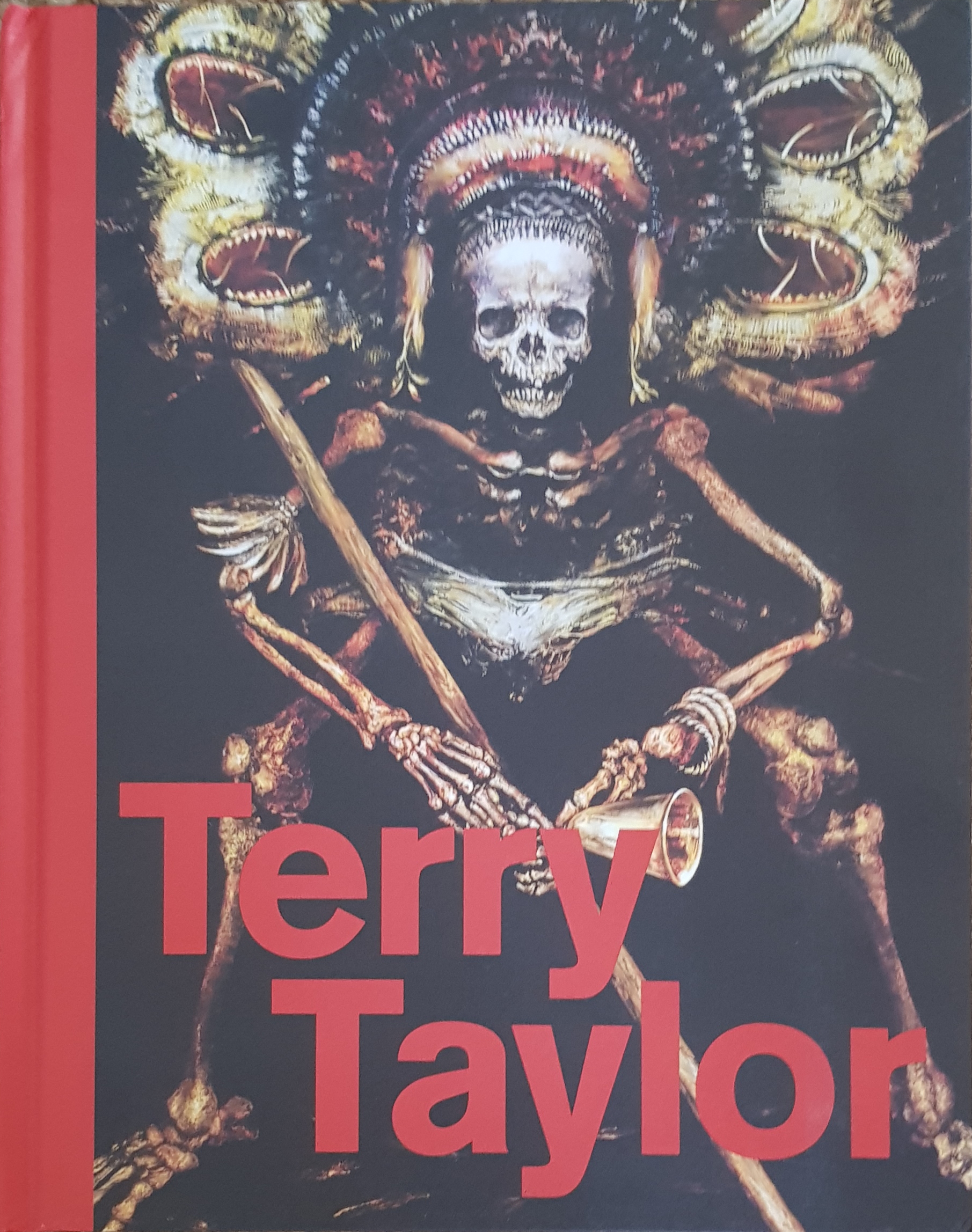

There was a time—we could identify it with the recent style of “millennial gothic”—when human skulls, like animal antlers, were the hippest designer artifacts. From haute couture jewelry to a black metal logo, this retro craze for the signature emblem of the medieval vanitas or danse macabre, ironically inverted in an exhilarating commodity form, was perhaps most notoriously exemplified in Damien Hirst’s diamond encrusted platinum cast of a skull as a pseudo-sacred relic, sardonically titled For the Love of God. But although skulls and skeletal remains pile up in Terry Taylor’s paintings in numbers and in configurations comparable to those in fantastic ossuaries and ancient catacombs, there is little in her art of that consumer fetish for bones that characterizes so much recent Gothicism. Taylor’s cast of the undead are far too lively and pugnacious to be either commercial talismans or voguish emblems. Her skeletons prance, pout, pose like centerfold models, leer, laugh, loom and madly as well as rudely gesticulate with the vigor of dangling and dancing skeletons in a fun park ghost-ride. Some of these figures—many of them portraits of the artist’s friends or of herself—can seem spirited in their antics, maverick and even likeable. They can adorn themselves and sport tribal as well as theatrical plumage. But, for all this verve, don’t take them lightly, certainly not as droll horror. They can also suffer and suggest violent and gruesome lingering deaths—crucifixion, impaling, dismemberment—with their remains displayed as if by some vicious despot as warnings or as war trophies. So often these bodies (although they can only barely be called that) disturbingly show vestigial, poignant and also piquant signs of life. A tongue juts from a gaping jaw, as if lapping at some food or in a carnal kiss, although there are no lips or skin on the face. Hair matted with blood or mud is flung like dreadlocks. Beady eyes peer from the recesses of a skull’s sockets with the glimmer of consciousness that obstinately refuses to go out. There is a sort of insubordination in this grotesque violence, and a sort of pluck or mad fortitude, suggestive of the dark humor of Goya rather than the hellish slapstick and farce of, say, the Chapman Brothers. And this darkness is eerily substantial. At first sight her figures appear to be brilliantly spot-lit against a viscous oily background with a dimensionless depth, like actors on an empty stage. Look again and the figures appear instead to be floating toward the surface of a bottomless black lake, like the revenant corpses of murder victims, like repressed traumatic memories or forbidden wishes that had been sunk into the liquid pit of the unconscious only to bubble obscenely back up. But look even more closely, in the way that Taylor’s seductive mastery of oil paint compels you to do, and you realize that this blackness is in fact the foreground, not the background, of the world she depicts. She paints in reverse, by scraping back and sweeping through molten sediments of color that swim beneath an encompassing blackness so fiercely reflective that it is a mirror. There can be no drawing underneath these images. Instead they are revealed, and with a virtuoso technique, by incising into a surface that is both obsidian in its mineralogical density and that unseals its content as if it were a syrupy secretion. It is the black mirror that reflects her own luminous image as she paints. It is the hell that she harrows. The death she descends into like so many lovelorn champions (Orpheus, Odysseus, Christ, Juliet) to summon and perhaps bring back those who have been unjustly lost.

EDWARD COLLESS